[ad_1]

It’s 8am on a blustery Tuesday and the emeritus professor of run-makin’ is out on the Devon moors rambling through the decades. After resting awhile at Headingley in 1991 and a few other points in between, he lands on 1981, and the memory of a hundred at Barbados in the shadow of Ken Barrington’s death which stops him in his tracks so suddenly that all I can hear is the whistling wind chasing the wisps of his voice. It’s already been a long and sprawling conversation. He pauses, apologises for his tears, and quietly and respectfully exits the call.

Barrington, forever draped in the union flag, was the “father figure and mentor” to a youngish, roguish bunch of England players on that West Indies tour, and Gooch loved him dearly. “A great man. We didn’t have a coach – technically he was our assistant manager – but he assumed the role of coach at the nets. He was a great guy to talk to, it was never about ‘his day’. He just gave you good nuggets of information.”

On the second morning of the Barbados Test, Gooch received a knock on his hotel room door. “Standing there was Both [Ian Botham, the captain] and Alan Smith the manager. I knew something was wrong because Both is never up at eight in the morning … unless he’s just getting in.” They told him that Barrington had died of a heart attack overnight.

He was no kind of age. He gave so much to cricket, wrote Wisden later that year, “that he left a few campaigners for the cause for the remainder of the 1980s. Even now as Gooch starts or finishes a drive or Gatting hooks, a memory of Barrington the batsman is stirred”.

The sense of a secret binding language running through the greats of English batting is never far from Gooch’s mind. It’s his life’s work to keep the conversation going. Alastair Cook, son and heir, has been listening in all of his life. Before him, Stewart and Atherton would do the same, absorbing the knowledge as best they could. These days Gooch sits on the cricket committee at Essex, and still they crowd around. To him, the act of making runs – and that’s making them, not merely scoring them, because, look, scoring runs is a doddle, anyone can do that on their day – is a sacred process; and little wonder, when we consider that no one in professional cricket has ever made as many as he.

Already down against superior opponents, Barrington’s death would crush that team. All except for Gooch, who made a fourth-innings hundred. “The one at Barbados is right up there,” he says. “Because of the feelings for Kenny, and the sense that I had to do something special for his memory. I can’t say it was an added incentive, because you should have an incentive every time you bat. But it gave me an … edge, you know?”

How do you find an edge when everything’s gone to dust? An edge, against Roberts, Holding, Garner and Croft? In the guts of trauma, internally wrecked, Gooch picked up his railway sleeper and excavated something good from a tragedy that even now brings him to a standstill. If we’re ever looking for a glimpse into what separates the good from the great, we could do worse than settle on this.

In a mass reservoir of runs – 172 professional hundreds – context becomes crucial. Another of his favourites, then, is the Lord’s hundred in 1979 to help Essex win the B&H Cup. “It wasn’t because I scored a hundred. But that was our first ever trophy. It remains a special moment for everyone who had an interest in us.”

Gooch had seen enough of Essex as “bridesmaids” and after Lord’s they would take over the county game. In 13 subsequent first-class seasons he made over 2,000 runs on five separate occasions, during which Essex won six championships. In 1996, by then aged 43, he was nearing the end: that season he hit eight hundreds at 67. “But it’s not about stats, OK? It’s never about that. It’s about when you supply that contribution. That’s what you should remember.”

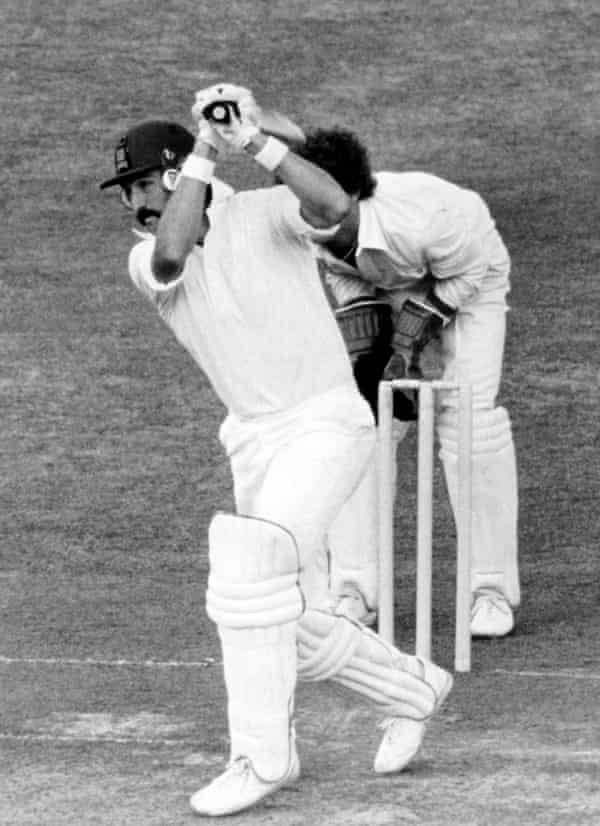

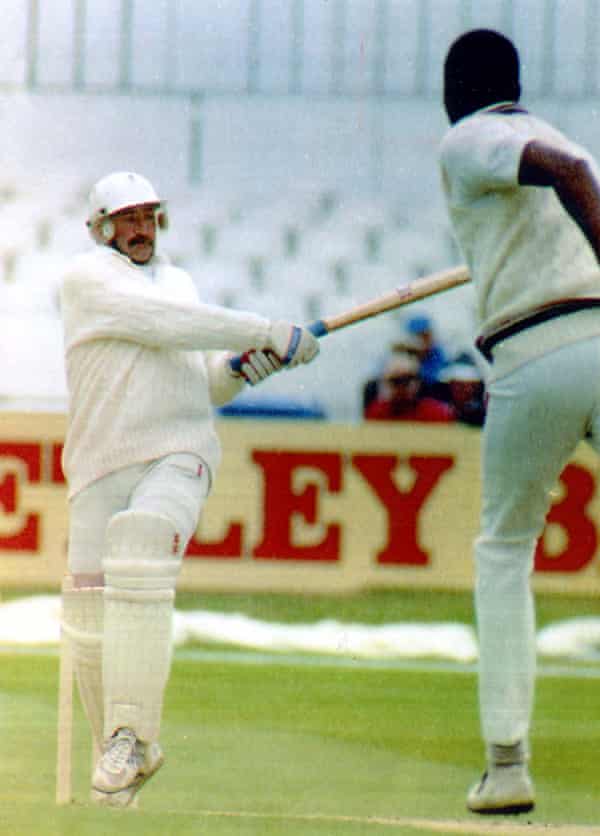

Three decades ago, Gooch built arguably Test cricket’s greatest innings. It was composed (his word) at Headingley, in the cold and dark, against a team that had not lost a match in England for 22 years. The team of Malcolm Marshall, Courtney Walsh, Curtly Ambrose, Patrick Patterson.

“We used to get changed in an old Seventies-style pavilion, and the nets were in front of that on the outfield. And you’d have all these good Yorkshire league bowlers coming along to bowl at us and they’d all have a point to prove, and it’d be jagging all over the place. The pitch at Headingley could be flat at times, but this one wasn’t, and the clouds were there scudding across towards the Pennines.”

Lord’s, The Oval, sun out, good pitch – they were batting grounds. “Headingley was the complete opposite. And that’s not a complaint, it’s just the way it was.”

It was also perishingly cold. “We were all in long-sleeved jumpers and I can tell you, I never batted in one of them. To score a hundred that was crucial to the game – and with us being under some pressure because our attack on paper was not as good as theirs – that was special.”

It’s typical of Gooch’s outcome-driven philosophy that any attempts to peel back the layers of this extraordinary feat leads instead to a symposium on playing late and soft. “First of all, just because sometimes you play and miss, it doesn’t mean that your technique is poor, OK? If you’re playing and missing a lot that doesn’t mean you’re playing badly – it can mean you’re playing well. If you present the bat with the right timing and hold your position, then if it jags, you will hopefully miss it. That’s good technique.

“The other skill is, there should be no energy on the bat if the ball does hit it. If you get there too early as a batsman you’re in trouble because you’ve made your position before the ball has completed its movement. The trick is, you get into your defensive position a split-second before the ball arrives. Then the ball hits the bat, you don’t hit the ball, OK? There’s no energy in the shot. If it cannons off the bat or the edge, it means you’re going too hard at it. It ends up in second slip’s hands. Take out the energy and there’s a good chance it’ll fall short of the slips and bounce first.”

There were some great shots in there too, of course: a clutch of cuts, the odd drive against the old ball, a few hooks late in the piece as he ran out of partners. On which: “The hook is a specific shot, OK? I know before Malcolm Marshall bowls whether I’m going to play the hook or not. What I’m telling you is, I’m making one decision or the other. I don’t understand batsmen who say: ‘I saw the ball dug in and I watch it come up, and then I decide whether to hook it or not.’ Well, you’ve got to be a fucking good player to do that, I can tell you.”

There’s more to it, he says – invoking the modern player’s ugly get-out clause – “than simply ‘see ball hit ball’. When you get a big score you compose and compile it.”

It’s getting through. Anyone can hit a good shot; that’s not the point. It’s the shots you don’t play, the misses that leave no trace, the risks you calculate, the scraps you escape from – these are the things that mark the real runmaker. After all, anyone can score runs. But can you make ’em? That’s the game right there.

This is an article from the June issue of Wisden Cricket Monthly in which various cricketers – including Gower, Edwards, Atherton and Pietersen – recall their best innings. Subscribe to the digital edition and pay just £2.99 for three issues, or to the print edition and pay just £5 for three issues.

[ad_2]

Source link