[ad_1]

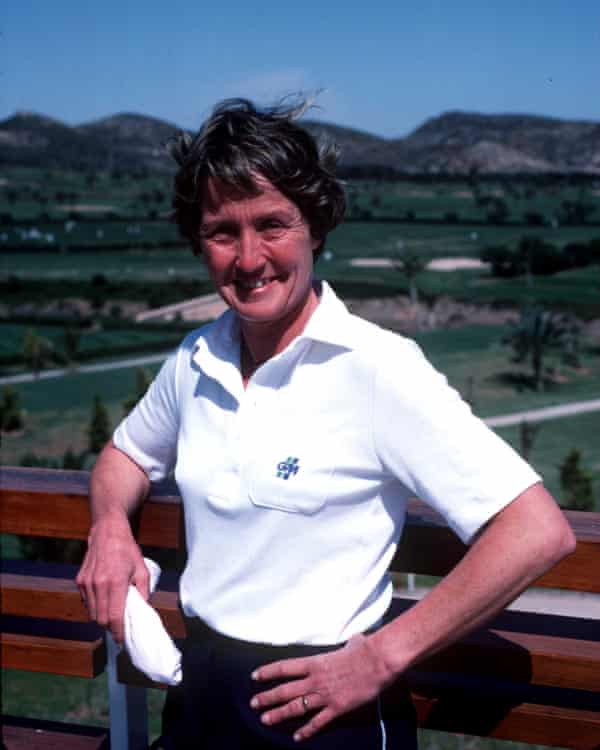

Sometimes you just have to go with the grand gesture. On Wednesday morning Marylebone Cricket Club will announce that it will be honouring Rachael Heyhoe Flint, the former England captain and pioneer of women’s cricket who died in 2017, by naming a permanent feature of the Lord’s ground after her. The Heyhoe Flint Gate, to be unveiled next summer, is the first piece of architecture at cricket’s hallowed headquarters to pay tribute to a woman. It will replace the current North Gate, the most popular entrance to the ground, well known to the millions of matchgoers who have made the walk down the Wellington Road, sandwiches packed and tickets in hand.

It is a fitting memorial to the first lady of English cricket, the woman who hit the first six in a women’s Test, batted for eight-and-a-half hours to save an Ashes series and pretty much invented cricket’s World Cup. But it is also a significant statement: the only other cricketer to have a gate named after him at Lord’s is WG Grace, the game’s greatest legend. Only in May gossipy journalists were claiming a new skirmish in the culture wars after a lone voice at an MCC members’ meeting complained he had heard the club might be erecting a statue to Heyhoe Flint. Imagine how he will feel when he finds out what it has actually done.

Full transparency is needed here: I am both an MCC member and on the club’s Heritage and Collections committee. But thankfully it is surprisingly easy to make the case that Heyhoe Flint has had as great an impact on the game as Grace did two centuries before her. The bearded one not only dominated the Victorian game as an all-rounder but influenced the way it was played and popularised it among a huge section of society, ushering in a new and increasingly democratic era for sport. Heyhoe Flint achieved nothing less. Throughout the 60s and 70s she was both her country’s best player and the unbeaten captain of the world’s best team. Her name has become linked with the women’s game the way Beyoncé’s is with lemonade.

It is true that considerably fewer people may have witnessed her pugnacious batting than saw WG. It is also true that WG did not come close to the selfless energy that Heyhoe Flint expended in advocating for the game at a time when she was repeatedly told that “girls don’t play cricket”. This is a woman who, through sheer force of will, opened up an all but exclusively male game to the other half of the population – not just in the UK but around the world.

Note, for instance, that MCC’s announcement is timed to coincide with the anniversary of the first women’s ODI at Lord’s in 1976. By this point England had been playing international cricket for over 40 years – and MCC never let women anywhere near its turf until the dogged Heyhoe Flint got after it.

She fought for fairness and equality without grudge or bitterness and with a consuming passion for the game that included the institutions that attempted to sideline her (it is a beautiful truth that her ashes were scattered on the Lord’s outfield). “She loved serving,” says her son Ben. “She loved a project and she wanted to sink her teeth into things that stood up for the women’s game. She just gave so much time to everything without any real need for compensation … Dad would always ask her, are you getting paid for any of this?” The answer, of course, was no. It is thanks only to Heyhoe Flint’s trailblazing that the generations of cricketers she inspired – from Clare Connor to Charlotte Edwards to Heather Knight – have enjoyed the resources, respect and compensation that women’s cricket never received in her own era.

As someone who was always more interested in getting things done than being applauded for it, Heyhoe Flint would probably be self-deprecating about this latest honour (last year’s domestic women’s tournament in England was also named after her). But the new Lord’s gate can stand for more than just her achievements. It can also be a permanent reminder of the long roll-call of female players whose names and contributions to cricket remain scandalously unknown, and whose portraits have never been hung in the Long Room – from the brilliant opening pairing of Betty Snowball and Myrtle MacLagan, to the miserly bowling of Jo Chamberlain, to the all-round genius of Enid Bakewell.

It is also a symbol of where women’s sport has come from and where it is at now. That is why this moment belongs not to the culture warriors but to those who, like Heyhoe Flint herself, prefer to take the long view. Some will applaud the MCC and some will complain that it took it long enough but in truth the best way to memorialise English cricket’s most important female figure has been under quiet and earnest discussion for a couple of years. Lord’s may not be a place where things happen fast, but it can be place where they happen right. Far better a gate than a statue. Far better a place where cricket lovers will tell each other to meet, a favourite spot where a cricketing legend’s name will live on, on the lips and in the texted instructions of friends and family as they join up with each other, excited for the game.

It is even a bit special that Rachael’s gate leads first to the Compton stand, given that the dashing Middlesex and England batsman was her sporting hero. “She really fancied Denis Compton,” says Ben. The design of the gates is still to be decided but the club says it is cracking on with it. And that is something its honouree would definitely approve of.

[ad_2]

Source link